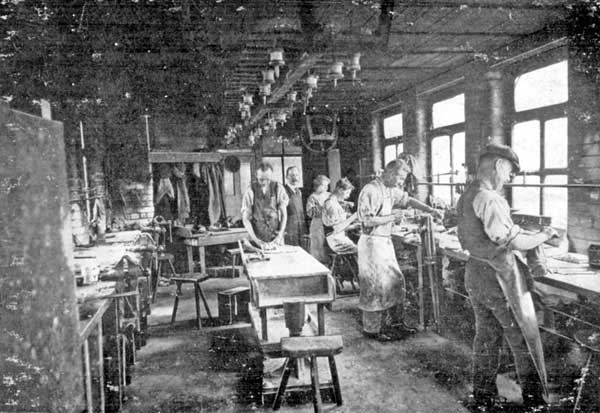

Unidentified Tableknife Cutlers Shop from Sheffield City Council’s Local Studies Library.

The Little Mesters of Sheffield made up a highly skilled network of craftspeople operating alongside (and amongst) heavy industries, declining notably following the Second World War.

Sheffield is famous as an industrial city, once known as the capital of the world for steel, cutlery and toolmaking. The heavy industries such as steelmaking and engineering often dominate the city’s image, which can overshadow the importance of Sheffield’s light trades. The light trades were very different in character and structure compared to the heavy industries, but were equally significant in Sheffield’s development. A large part of this significance was due to a network of craftspeople known as the ‘Little Mesters’.

The origins of the term ‘Little Mester’ are uncertain, but it is used to refer to a particular kind of craftsman in the town of Sheffield and the surrounding area. Often described as the backbone of Sheffield’s cutlery and toolmaking industries, the Little Mesters enjoy a reputation as highly skilled and specialised workers. They worked for themselves, sometimes alone, and sometimes employing apprentices or another worker or two. At the height of their population in the mid 1800s, they were making a vast contribution to the variety of products with a Sheffield stamp on. Today, there are a handful of these craftsmen left in Sheffield, and the future for the continuation of their skills is looking uncertain. BBC Legacies.

With the decline of the Little Mester, museum curators, archivists, and local historians have begun to document the few remaining workers, and place the legacy of the Little Mester in the context of Sheffield’s history. Nick Hand has produced a photofilm of one the few remaining Little Mesters, Trevor Ablett, who makes penknives in the workshop he shares with Reg Cooper.

Outside of this work, and the BBC Legacies piece, Martin Pick has compiled a photobook capturing the remnants of the industry at the turn of the millennium and Made in Sheffield produced a short overview of Sheffield’s Little Mesters. The latter piece is no longer accessible, so I’ve copied the rest of it (from Archive.org) below:

What is a Little Mester?

The Little Mesters were the backbone of Sheffield’s cutlery industry and were instrumental in helping the city achieve its worldwide reputation for quality craftsmanship. The phrase Little Mester is a regional term used to describe Sheffield’s self employed cutlers who rented space in factories and had their finished goods sold by the factory owner. However the term is also more widely applied to almost any self-employed craftsman working in steel or metal.Little Mesters were an essential part of the unique system of organisation that developed in the cutlery industry during the late eighteenth century. Before this time cutlers made their wares through to completion and were responsible for finding their own markets. But the trade boom of the late eighteenth century led to a huge diversification of products and saw the introduction of specialisation.

Little Mesters and the Cutlery Industry

Each type of knife now required three different specialist craftsmen to complete the job. The forger fashioned the blade, the grinder gave the blade its edge and the cutler finished the blade and fitted the handle. This system was co-ordinated in one of two ways – by cutlers or factors.Cutlers who could afford to obtain commissions from forgers and grinders were able to complete the item and sell it themselves and many cutlers became very prosperous. But the more usual method was for factors (people with capital who hitherto had been outside the cutlery industry) to farm out the work to craftsmen and then sell the finished goods under the factor’s name.

As these large firms and master cutlers did not usually hire workers directly, hundreds of self employed Little Mesters and their assistants would produce goods on their factor’s behalf. The Little Mesters could still undertake work for any factory they wished even if they were renting space in another company.

The system may sound unusual but it was perfectly suited to the cutlery industry of that time and proved very flexible. The Little Mesters were free to work for whoever they chose and were not tied to any one company, while the factors were able to satisfy bulk or specialist orders without high overheads.

Decline of the Little Mesters

The increased mechanisation of the cutlery industry during the twentieth century, particularly after the Second World War, inevitably signalled the decline of the Little Mesters. But in the face of mass production and competition from abroad, Sheffield craftsmen continued to use traditional methods as much as possible.This somewhat misplaced fondness for the era of hand made goods was not much of a defence against the cheaper cutlery being manufactured overseas and the number of Little Mesters dwindled accordingly, from around 300 in the 1940s to only around 20 in the 1960s.

Today a few of Sheffield’s remaining Little Mesters can be seen in action at the city’s Kelham Island Industrial Museum in reconstructed workshops. These specialist craftsmen include a custom knifemaker, blade grinder, dental and surgical instrument maker and a forger of surgical instruments.