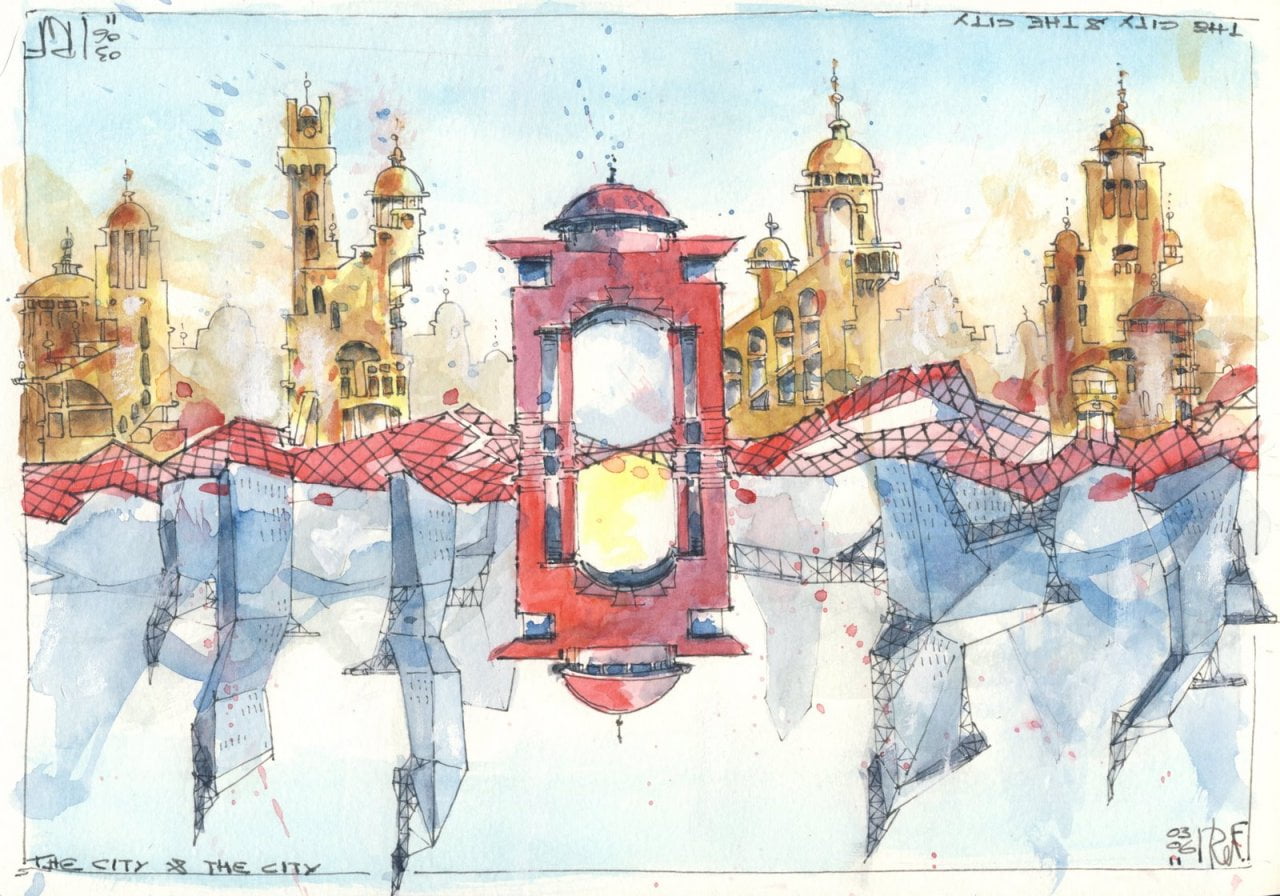

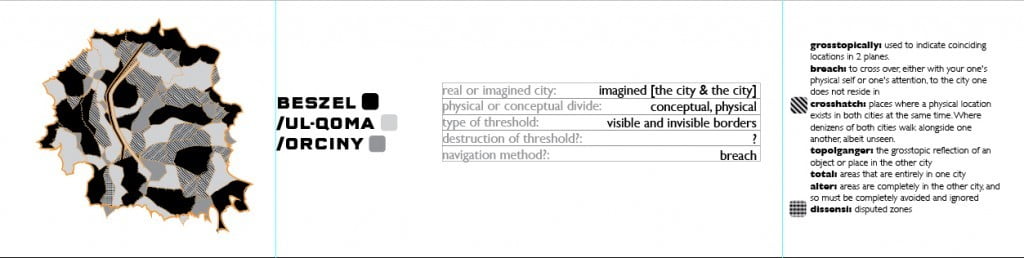

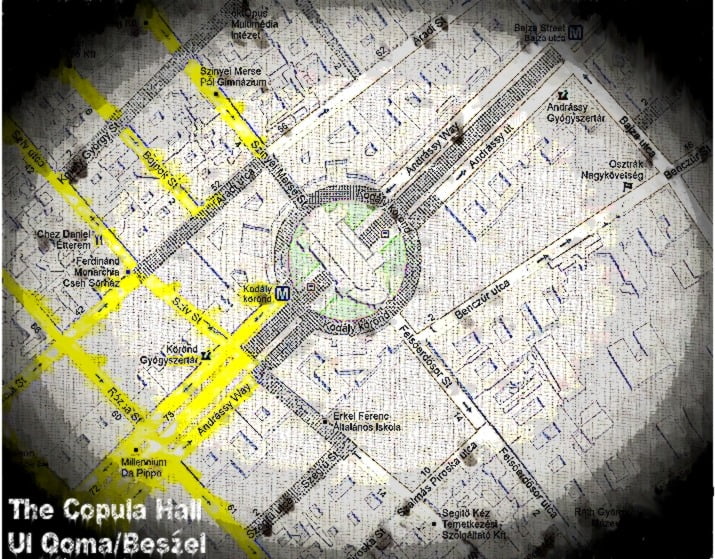

The border that separates Besźel from Ul Qoma is notable in its absence from geography. The cities overlap, differentiated only by the colors and designs of their building, the dress and habit of their people. This literal manifestation of the “wall in the mind” requires one city’s inhabitants to learn to not recognize the other, and vice versa. Border crossing can only take place at the designated border zone at Copula Hall, where emigrants circle back on the same space, but enter into an altered perceptual place. Transgressing this arrangement is punishable by the seemingly otherworldly phenomena of Breach, but it is in exactly this kind of transgression that the story seems to set its motions.

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious to what extent you were hoping to base your work on these sorts of real-life border conditions.

Miéville: The most extreme example of this was something I saw in an article in the Christian Science Monitor, where a couple of poli-sci guys from the State Department or something similar were proposing a solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. In the case of Jerusalem, they were proposing basically exactly this kind of system, from The City and The City, in that you would have a single urban space in which different citizens are covered by completely different juridical relations and social relations, and in which you would have two overlapping authorities.

I was amazed when I saw this. I think, in a real world sense, it’s completely demented. I don’t think it would work at all, and I don’t think Israel has the slightest intention of trying it.

My intent with The City and The City was, as you say, to derive something hyperbolic and fictional through an exaggeration of the logic of borders, rather than to invent my own magical logic of how borders could be. It was an extrapolation of really quite everyday, quite quotidian, juridical and social aspects of nation-state borders: I combined that with a politicized social filtering, and extrapolated out and exaggerated further on a sociologically plausible basis, eventually taking it to a ridiculous extreme.

But I’m always slightly nervous when people make analogies to things like Palestine because I think there can be a danger of a kind of sympathetic magic: you see two things that are about divided cities and so you think that they must therefore be similar in some way. Whereas, in fact, in a lot of these situations, it seems to me that—and certainly in the question of Palestine—the problem is not one population being unseen, it’s one population being very, very aggressively seen by the armed wing of another population.

In fact, I put those words into Borlu’s mouth in the book, where he says, “This is nothing like Berlin, this is nothing like Jerusalem.” That’s partly just to disavow—because you don’t want to make the book too easy—but it’s also to make a serious point, which is that, obviously, the analogies will occur but sometimes they will obscure as much as they illuminate.