This is a draft of a talk I delivered at the Maintainers II: Labor, Technology, and Social Orders Conference on April 6-9, 2017 as part of our telephone panel, “Dial M for Maintenance,” with Shari Wolk, Joshua Bell, and Fabian Prieto-Ñañez.

The telephone may seem to be the pre-eminent emblem for the history of innovation. There is perhaps no story that rings more clearly with the triumph of invention than the one given by the vibration of voice on the end of the line: “Mr. Watson—come here—I want to see you.” This was, after all, what was recounted in nearly every publication by the company for the next fifty years, this is what was reaffirmed by the contentious patent dispute that rendered Bell, not Gray, the “inventor of the telephone.” But the grant account of invention leaves only a singular sort of structure. If the existence of the telephone presupposes the existence of another telephone, it must also presuppose the work of the men and women who kept up the connection between them.

Maintenance is the work of repairing and refurbishing faults in technological systems. To reaffirm shopping as a maintenance practice, then, it is necessary to recognize that it must also be the work of organizing the materials that are necessary to sustain them. It is the work, one might say, of supply. And despite the myth of its making, nowhere has this been more true than in the history of telephony, where the “invention” of the telephone transformed the Western Electric Company from one of the most formidable producers of electrical and telecommunication equipment to an entity driven almost entirely by the demands of maintaining the system it had brought into being. The telephone network required not only the production of the sets supplied to its subscribers, but the maintenance of the switchboards and lines they now depended on. It required a diverse array of human agents and an extensive supply of nonhuman ones. To furnish them, Western Electric came to manage one of the most expansive purchasing operations in the world. Shopping for the system, its stewards explained, was no simple task.

Under the 1882 arrangement that brought it into the Bell System, Western had not only become the sole manufacturer of the telephone, it had begun the transition to the principal purchasing agent and “one source of supply for the Telephone Company.” The result, I would suggest, was that the business of maintenance became the business of the firm.

The Supply Department

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the scale of the materials required for the function of the telephone network had become something of a concern, even within the seemingly ordered operation of the Bell System. Nineteenth-century sourcing had been a largely haphazard affair, without the precise specifications needed to meet the requirements of manufacture and maintain the complex geographies modern operations required for their persistence. By 1920, even the minimum requirement for maintaining the telephone totaled tens of millions pounds of copper, tin, and lead; tens of thousands tons of galvanized iron and steel wire, pole line hardware, and paper for directories; and tens of millions feet of lumber and clay conduits.1 Monopoly leverage, Albert Salt, Western Electric’s general purchasing agent, explained in 1914, as “the country’s largest electrical jobber,” had helped to some extent, extending Western’s material demands into the farthest reaches of the supply chain.2 Specifications “prepared by the engineering department” were now “usually accepted as standard,” and in some commodities the company had become the single largest purchaser and distributor in the world.3

This hadn’t always been the case. Before the turn of the century the regional telephone companies had operated their own purchasing and supply departments. The only thing the “average telephonic man knew [then] about supplies,” E. J. Speh, superintendent of supplies in Philadelphia, wrote in 1912, “was that he usually did not have the articles he needed when he wanted them.” After joining the System, all of the switchboards, telephone sets, “and a great deal of the wire, cross-arms, and supplies of that kind” could be bought from Western Electric, and Speh estimated that by 1900 sixty-five percent of all the material was provided this way. “It appeared logical,” he offered, that Western was in “the best position to undertake the purchasing for all associated companies.” Under this arrangement Western would manufacture and sell all the materials that were requested, repair or reissue equipment when it was needed, and “establish warehouses in locations suitable for a proper distribution of supplies.” In short, “it undertook all of the functions of a Supply and Purchasing Department.”4

As Speh saw it, the regional telephone companies had been akin to “a chain of retail stores whose customers are the lineman, installers, and other workmen who use material to build and maintain the telephone plant.” As a result, they had found themselves with many of the same problems that retail operations like “Woolworth five and ten cent stores” might have. The daily practice of making local inventories and estimates, formulating overstock reports, overseeing minor repairs, and preparing requisitions had become a critical point of failure in maintaining the larger system of supply. Sometimes the regional operations were carefully organized. Sometimes not. One of the storerooms Speh encountered in 1910, for example, had a “prize catch-all” which contained these supplies, valued at $17.44:

Receiver headband, directory, ringer and gong, generator, junk wire. worn-out dry batteries, new No. 87 cords, new No. 96 cords, induction coil, mouthpieces, No. 156 cords attached to No. 110 plugs. No. 12-A protectors, glass insulators, copper sleeves, test connector, bolts, bit, solder, leather strip, fiber tube, assortment of screws. From the perspective of the telephone companies it was necessary to perform their duties only to the extent that they could “assure a regular replenishment of stocks by frequent order upon the Western Electric Company at frequent intervals.”5

The expansion of Western’s operation wasn’t as easy as Speh would seem to suggest. As then-president of Western Electric (and future president of AT&T) H. B. Thayer explained it in 1913, Western had at first been so reliable that there was a great deal of uncertainty when it now failed to function.6 To concerns over unmet demands, unexpected delays, or unclear accounting, supply men like the Chicago’s H. H. Henry could only affirm the incredible scale and nearly insurmountable challenges undertaken in the work of provisioning. Despite the well-ordered appearance wrought for the standard requisition, the logistical demands inscribed on their redemption as “W. E. Material,” were substantial. To the unhappy impression left by “liberal sprinklings” of the “Black Order’” mark on delivery tickets, Henry offered that “it may be interesting to know that the Supply Agent’s office is not established for the purpose of holding on to supplies, or to block orders for any material authorized for use.”7

As he wrote to the regional services, supply houses, distribution centers, repair shops, and sales agents of the System, Henry struggled to illustrate the function of the forms necessary for Western’s circulation of supply.8 His need to do so was suggestive of just how quickly Western Electric had become associated with the promise of provision. In some sense, the entirety of telephony had collapsed under the formal designation of the order requisition, a singular mechanism of procurement for Speh’s “one source of supply.”9 “Now with the material on hand, or scheduled, how are we to get it?” Henry asked. The answer, it seemed, was always the same. “Whether the material desired is cable or terminal boxes, pencils or printed forms, desks or chairs, soaps or mops—’Make a requisition for it.’”10

The Requisition

The work done by the requisition served to abstract out decades of work done by purchasing agents through the turn of the century. They not only worked to regulate and routinize the actions inscribed on them, they mediated Western’s interactions by directing particular presentations of its corporate role. To H. H. Henry and his readers, it was not Western Electric the manufacturer, but Western Electric the “storekeeper,” the distributor, the collection of accountants and acquisitions men, who would carefully scour reports and records to build up stocks and estimates. It was Western Electric the supplier, with the Western Electric News writing of how its traffic department did the work of “routing shipments from the hundreds of points of supply to distributing houses and customers,” moving “nearly a million tons of freight each year” across tens of thousands of shipments (by 1917 it was “one billion, eight hundred million odd pounds”). If the heart of the company had been at its factory in Hawthorne, its nerves were now spread among the countless supply and distributing houses (nearly thirty) responsible for running investments in stocks and managing deliveries.11

The requisitions they issued were connective, adhesive, forms. They not only brought together their disparate divisions, they forged the distant links of a global supply chain, holding together the business of buying and the materials of supply until their ultimate installation by telephone technician at the site of subscription. Under the weight of the supply contract the Western Electric office had become a sprawling assembly of diverse sites: the stock maintenance desk that must secure the material summaries serving as estimates of requirements, authorize stocks, and supervise changing of printed forms; the service desk that charted telegraphic and written inquiries for orders before filing claims on discrepancies; a credit desk where inspectors saw returned goods passed in exchange for credit; the billing desk term stamping orders cross-referenced against the bound copies of the company’s purchase agreements.12

“One Order Covers Them All!” 1924.

A myriad of considerations went into the filling of these requisitions and the handling of their receipts, bills, and credits, byzantine procedures that stood in stark contrast to the clean lines of their initiating forms. It was in this disjuncture that all manner of frustration could be found. Upon receipt requisitions were sorted and distributed to Western’s various “editors.” These men, “who must interpret the requisition” and decipher the meaning of its margins, relied on a combination of guesswork (although “experience has taught him that it is not safe to guess at what is desired”), catalogues, and prior receipts to ascertain intent and rework the requisition—or more often, as these examples suggest, flag it according to its descriptive deficiencies:

Requisition calls for cable boxes No. A-104379. Edited it will be necessary to know what finish, oak or mahogany.

Requisition calls for generator or motor-brushes, size given, but no serial numbers of machines are shown. The correct brushes cannot be furnished without this information.

Requisition shows Tungsten lamps, 110 volts. Before order can be entered it is necessary to show what wattage is wanted (25, 40 or 60).13

In response to these inquiries requisitions could quickly disband into the convoluted network of notations, telephone calls, and telegraph wires that supported them. Rarely would a requisition be plain and unadorned, absent the idiosyncratic instructions of their authors. Class C material (repaired and refurbished), for example, was often preempted with the familiar notation, “do not substitute.”14 While requisitions may have held a formal quality in the company’s books, they depended on an informal array of supplemental communiqués to produce their desired effect. Readers who would “take the business of supply into their own hands,” Henry wrote, would be well served to anticipate and send requisitions by telegram (and, though it was rarely said, by telephone). “It is surprising,” he remarked, though it should not have been, just how many were received.15 But wherever telegrams were sent or telephone calls placed, paper requisitions had to follow. Once they had been analyzed and edited, resubmitted and re-reviewed, these requisitions were coded and transformed into an order ticket sent to the warehouse or distribution center, to either Hawthorne or New York, the telephone companies C Stocks, or purchased from outside suppliers. The vouchers that they initiated formed their own dense network of index and inventories, parts lists, and catalogue abstracts, a vast and interconnected chain of paper cards and telegraph cables tasked to stand in for the countless suppliers with whom Western worked.16 These forms were second order operators, and no longer content to stand in for people or things, they now replaced entire sequences of operation.

At the beginning of the 1920s the voucher section at Hawthorne issued checks for about three and a half million dollars to settle its external material bills every month, about $146,000 a day, or $18,250 each hour of every working day—”a five-dollar bill every time the clock ticks off a second.” The Western Electric News suggested a person “could buy almost everything with that much money.” It was enough to say that Western bought “almost everything from almost everywhere,” a shopping list comprised of “Indian mica, Turkish emery, Norway iron, South American asphalt, crude rubber from Africa, South America, Mexico, Ceylon, Borneo and other tropical lands; whale oil from wherever the whale happens to be; lard, leather, bank-note paper, rhinoceros hide, dyes, chemicals of all kinds, felt, tape, jute, [and] silk. In short, “everything from dirt to diamonds.” It was so complete that a member of the purchasing department, the Western Electric News reported, had once made a bet with a man “who thought he could name three things the Western Electric Company had never bought.” He couldn’t.17

All in the Day’s Marketing

While it had at first bristled under the constraints of the supply contract, by the middle of the 1920s Western began to position itself as a kind of universal supplier. But it had been some time before it began to consider the place of the telephone in this arrangement. Few of its earlier publications afforded the phone any particular kind of impact in the purchasing process at all, and it is almost remarkable how slowly the company manufacturing the telephone came to the realization that this was the very communicative connection that could collapse the entire system that had preceded it. It had been obvious to some businessmen as early as 1905 that, in concert with the catalogue, the telephone could provide a powerful mechanism of demand. Frank Lomas wrote that, with the “growing use of the telephone in country districts,” not only could the regular customer “notify his merchant if goods he has purchased are not what he wished,” but “he can send in his order, and have it booked almost as well as though he were there,” sent out by the delivery man to his door.18 Once this realization came to Western, it would envelop the whole of supply and distribution. Western Electric would not only be a supplier of materials, they would be the supplier of suppliers.

“Open This Door to Your Biggest Stockroom,” 1924.

“If your dealer cannot supply you,” their publications increasingly emphasized, “we will.” As early as 1909, they had already begun to offer 24-hour shipments of “poles, pins, cross-arms, insulators, wires,” among other items. Line construction material could be had “when you want it.”19 While not every component was offered with such appalling efficiency, many would soon be. While the 1915 Voice Highways conceded that some cables would sluggishly ship “three to four weeks” after receipt, “certain types” could be sent immediately—and more each year. While the company had then claimed “thirty distribution houses,” the Telephone Register records forty-two by 1924, and its Supply Year Books at the end of the decade, fifty-two. These networked nodes of supply, backed by the Hawthorne Works, its new site at Kearny, and countless warehouses, made the company a universal emblem of availability. Some of the company’s notices asked businesses to “make your order book—your store house,” to “supply your needs” with “everything electrical” under one cover. Others suggested that businesses might have had resources they didn’t even know about. One example was “an electrical supply room within easy call,” but which “might as well be locked.” Behind the door, they wrote, was the Western Electric Distribution House, a “source of supply” ready to stand as “your own reserve.”20

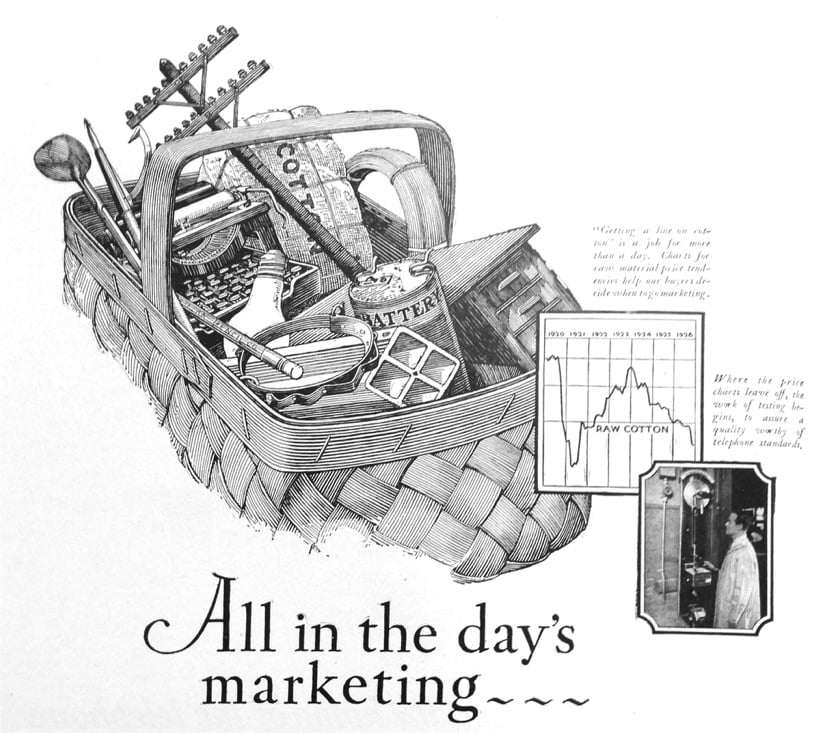

The human representatives of the organization were no longer the factory workers at Hawthorne, or linemen stringing wire—they were the purchasing agent and the dealer. It seemed that purchasing could become an almost transcendent and all-consuming act. Markets replaced by marketing. Not “mere buying,” the Western Electric man sets out upon a “vast and fascinating task,” requiring “keen judgment, extensive research, and scientific planning” to ensure “adequate sources of supply.”21 In the work of “backing up your telephone,” Western spoke of buying rubber from Singapore, mica from India, and conduit from Ohio. Like the “story of silk” it would capture in its 1920s “material series,” Western advertised how it found the source for the telephone’s insulation in the mulberry bush. All the better to illustrate the “huge market basket” that Western now carried. From “pencils to telephone poles,” in “go pins,” in go “locomotives,” but nothing bought “without investigation of world-wide sources of supply.” From telephone poles to precious metals, stocking the Bell system “calls for imagination,” for “minds unshackled” in their global search for supply.22

“All in the Day’s Marketing,” 1927.

The telephone now offered a way of encapsulating the maintenance of production into a singular point of call, enrolling scores of businesses and agents within a subscription of supply. Notices that appeared in the 1925 Manufacturer’s Record offered a cure for the “purchasing agent’s nightmare.” While the world’s “champion bookworm” may be the purchasing agent of an industrial plant, even he, Western suggested, “must be appalled by the mass of catalogues and sales literature which confronts him every time he wants to buy something.” In answer, Western suggested itself as the “center” of an electric exchange that could relieve him of the “burden of buying,” searching markets “the country over” with “exacting specifications.” For purchasers and storekeepers, supplies were now “ready at your call.” The telephone transformed order books, catalogues, and the distant sites of directories into telephonic storehouses.23 As the 1930 “Telephone Almanac” suggested, only the telephone that could place its users within earshot of over “29,500,000” others, in “more than a score of widely separated lands.” Only the telephone that could enable “merchant or manufacturer” to send their words “more than one-third of the way around the world,” to bring “within arm’s reach the trade of markets thousands of miles away.”24

Telephony had always tended toward a particular kind of synchronicity in its communication. Speech had demanded an immediacy of listening, of response, that Western could now align to the particular perception of system and efficiency it had long struggled with. This was premised upon the strange acceptance of its listeners that the movement of the telephone, that is to say the movement of the vocal cords and of speech entering the receiver, of maintaining the system that supported it, was somehow a kind of non-movement. When the regional Bells and external clients now came to speak to Western Electric, they spoke only to Western Electric. All that happened was that it listened, and “The Western Electric Gets it,” as H. H. Henry had written:

An attorney called upon to address a class in “Commercial Law” announced as his subject “What becomes of a man’s money when he dies” and was very promptly and unexpectedly answered by a voice from the rear, “The lawyers get it.” Undoubtedly if the question was asked of the average telephone employee, “What becomes of your requisitions after they are made out and approved,” the answer would be, “The Western Electric gets them,” and further than that little could be said.25

By the end of the decade, it was clear that this identity would be what remained in the years to follow, as Western’s abilities as an innovator, and its interests in electricity, were spun out to the newly formed Bell Laboratories and the Graybar Electric Company. There is a sense of loss here, a pleading in the company’s later advertisements, from the domestic images brought out for Western’s “market basket” to its position “backing” the telephone system. Personified in the character of a shopping switchboard, it seems uncertain of the position it has found for itself. “I’m the manufacturer for the Bell System, too,” it says, struggling to be heard—almost drown out by the silent work of shopping for the system.

Notes

-

Western Electric, “Supply and Demand,” NMAH, 1920. “75,000,000 pounds of copper, 10,000 tons of galvanized iron and steel wire, 12,000 tons of pole line hard-ware, 100,000.000 pounds of lead, 1,000,000 pounds of antimony, 700,000 pounds of tin, 10,000,000 pounds of sheet and rod brass, 15,000 tons of paper for directories, more than 24,000,000 feet of lumber, 12,000,000 feet of clay conduits, and 10,000,000 glass insulators.” ↩

-

Salt oversaw a veritable army of offices and operatives in service to this supply. Among his assistant general purchasing agents, there was an office in New York (telephone supplies, directories, stationary, and foreign factories), one in Chicago (Western suppliers and Hawthorne), an agent who dealt with timber supplies and telephone poles, and a separate division for handling electrical supply. ↩

-

Albert Salt, “The Purchasing Department—Its Function and Organization,” Western Electric News 3, no. 2 (April 1914): 1-3. Namely in “copper wire, iron and steel wire… cross-arms, [and] pole line hardware.” Salt would go on to become the first president of Graybar when it was first formed in 1925. See Richard Blodgett, Timeless Values, Enduring Innovation: The Graybar Story (Old Lyme, CT: Greenwich, 2009). ↩

-

E. J. Speh, “Betterments in Supply Work,” The Telephone News 8, no. 3 (February 1, 1912): 3-7. ↩

-

E. J. Speh, “Betterments in Supply Work,” The Telephone News 8, no. 3 (February 1, 1912): 3-7. ↩

-

H. B. Thayer, “The Western Electric Company and Its Relation to the Bell System,” Bell Telephone News 6, no. 3 (October 1916): 5-8. ↩

-

H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 6-7. ↩

-

H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 6-7. ↩

-

E. J. Speh, “Betterments in Supply Work,” The Telephone News 8, no. 3 (February 1, 1912): 3. ↩

-

H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 6-7. ↩

-

“Seeing That It Gets There,” Western Electric News 6, no. 4 (June, 1917): 3-6. First among these distributing houses was Philadelphia in 1901, to be followed by St. Louis, Denver, Kansas City, San Francisco, Illinois, Cincinnati, New York, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Indiana, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Seattle, Boston, Dallas, Michigan, Portland, Cleveland, Houston, New Orleans, Connecticut (New Haven), Washington, Milwaukee, Long Island (Brooklyn), New Jersey (Newark) and finally Jacksonville in 1927. Albert B. Iardella, ed., Western Electric and the Bell System: A Survey of Service (New York: Western Electric, 1964). ↩

-

H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 6-7.

-

H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 6-7. ↩

-

Class C Stock includes items awaiting repair, as opposed to stock in service or ready for general supply and distribution. It was used as both a general name for the work of repair, and to humorously describe something (or someone) as out of date, broken, or otherwise in need of mending, e.g., “Put him in Class C stock.” Western Electric News 10, no. 1 (1921): xxi. ↩

-

“Ship by express today, requisition 1610 being mailed”; or perhaps within a few days after receipt of requisition, “When may we expect delivery on requisition 677, holding up work.” H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 7. ↩

-

Voucher systems of this sort, handling distribution of purchasing through internal divisions and into external suppliers, had been used extensively by the railroads. It had become increasingly common in integrated firms (notably Carnegie Steel). Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977), 267. ↩

-

“The Long Green and the Red Tape,” Western Electric News 6, no. 12 (February 1918): 14-15. ↩

-

Frank Lomas, “How the Country Merchant Meets the Competition of the Catalogue House,” in The Book on Selling, The Business Man’s Library, vol. 4 (New York: The System Company, 1905) ↩

-

“Western Electric Service,” “Line Construction Material” and “24-Hour Shipments,” NMAH, 1909. ↩

-

It was ready, they suggested “for your regular and emergency demands” with “everything from the bottom of the hole to the top of the pole.” “Everything From the Bottom of the Hole—To the Top of the Pole,” Western Electric, “Locked!” and “Make Your Order Book Your Store House,” NMAH, 1924. A later example along these lines is “Some Lamp Storerooms You Didn’t Know You Had” from 1929. ↩

-

Western Electric, “In Case You Think That Purchasing Merely Means Buying,” Western Electric College Papers, no. 102, AT&T Archives, 1930. ↩

-

Western Electric, “”Backing Up Your Telephone,” NMAH, 1930 and “Manufacturers… Purchasers… Distributors…” Western Electric College Papers, no. 108, AT&T Archives, 1930. ↩

-

Western Electric, “Purchasing Agent’s Nightmare—And How to Cure It,” NMAH, 1925. ↩

-

AT&T, “Telephone Almanac,” AT&T Archives, 1930. ↩

-

H. H. Henry, “The Work of the Supply Department,” Bell Telephone News 2, no. 7 (February, 1913): 6-7. ↩