This Spring 2018 conversation with Matthew Hockenberry originally appeared on Public Seminar. It marks the beginning of a series of dialogues on the subject of logistics. No longer a mere subject of business management schools or an exclusive expertise of the military, logistics has become a significant presence in recent scholarship, particularly in the humanities, and is now frequently talked about in fields such as geography, information studies, international relations, and media studies. In its simplest definition, we might say that logistics is the management of the flows and circulation of goods, ideas, and peoples, with a typical emphasis placed on efficiency and optimization. In its everydayness, it is what determines who lives in a world of two-day deliveries, who doesn’t, or what products may be shipped faster than others. All this is dependent of course on where things may be produced or stored, who the products are being shipped to, and what the political and economic relationship might be between one point and another. We might therefore also recognize logistics and its geopolitics playing out in China’s Belt and Road initiative, building new railroads and ports to remap the present landscape of material distribution and consumption. All this is to suggest that logistics may for all intents and purposes appear to be fairly banal, as most media and infrastructures are; but it is nonetheless encoded with its own politics and affordances, like most media and infrastructures.

Kenneth Tay (KT): By way of introduction, I thought we could begin by talking about Supply & Command, the conference that you co-organized this past April. For me, the conference was a timely one, given the growing interests and scholarship on the infrastructures and supply chains that support the circulation, production and consumption of our media content and devices — as well as the aesthetics of these supporting systems. You opened the conference by citing the work of media scholar John Durham Peters, in suggesting that media have a logistical function of coordinating people, ideas, and things across different arrangements of time and space — not all that different when we think about supply chain management. But what I found most haunting in the opening roundtable of the conference was your question: “Are all media logistical? Where does that stop?” Could you talk a little about this question, and why perhaps there might be a limit to such a proposition of media as logistical?

Matthew Hockenberry (MH): The idea of logistical media, as it has been articulated by John Durham Peters and Judd Case, and which has some precedence in work of scholars like James Carey, Lewis Mumford, and Paul Virilio, centers on the relationship between media and communication. Peters describes it as media which “arrange people and property into time and space,” prior to, and forming, “the grid in which messages are sent.” Logistical media, then, are the means of orientation, the way in which time and space can be made and measured. It is through structures like calendars and clocks, lists and ledgers, that the patterns of communication, calculation, and control begin. And this definition has been taken up to some degree by people like Ned Rossiter, who considers how media forms coordinate the movement of lives and labor in the global supply chain, and Liam Cole Young, who finds in the logistical form of the list a device that “mediates boundaries between administration and art, knowledge and poetics, sense and nonsense.” But I think for a lot of people in media studies, things like calendars and clocks — even Case’s work on “bureaucratic and militaristic” technologies like Radar — seem a world away from our understanding of things like literature, painting, television, and film.

So I think the question here is not so much what the extent of mediation as a logistical operation might be, but what it is we hope to get out of the sort of thinking that begins with the intuition that all media are logistical media. From my perspective, to say that there is something common to writing romance and writing receipts is to advance a view of mediation that works to reincorporate the coordinating capability of all media forms. It allows us ask questions about how we reconcile radio as a military means for ordering “men and materials” alongside its history in broadcast news and entertainment. Or to wonder if it makes sense to focus on film production as a logistical operation, considering its necessary assembly of places, people, and props. One might say that we should be thinking of television the way Peters thinks of clock towers, as providing a point that people look towards — even if it is an emotional or cultural, rather than temporal, sort of orientation. I’m motivated here by the work of people like Lisa Gitelman, work that encourages us to think of media expansively, but understand what we get out of that expansion. Perhaps we might add to “orienting” another logistical operation, “assembly.” Jonathan Sterne, for example, references Lewis Mumford’s description of “container technologies,” the forms that move, and necessarily assemble, things from one place to another, to explore the relationship between sound format and sound. Mediums are container technologies, moving images and sounds from here to there, but Sterne doesn’t leave it here. They are “not like suitcases,” he says, and “images, sounds, and moving pictures are not like clothes.” Because they have “no existence apart from their containers and from their movements — or the possibility thereof,” you can’t extract the “content” of a medium from the infrastructure required for it, or the logistical function it provides. Representation is irreducible. If all media are logistical, then perhaps some orient, and some assemble.

The other side of this is what it means to say that logistical operations are mediative ones. For example, in that opening panel Dara Orenstein pointed to the debate about whether or not “assembly” is transformative. Assembly is often taken to have this lesser sense of value — movement without meaning. But perhaps it is, in itself, transformative. Consider that western companies seem particularly invested in the idea that there is little difference between different sites of assembly, and the different workers, cultures, and countries that comprise them. But this is entirely a question of mediation. What processes of production “count,” and which don’t. Design yes, soldering no. It isn’t incidental that this divorces them from many of the unfortunate entanglements of their operations.

KT: Yes, and as someone just coming into the field of media studies, I’ve found this expansive thinking about and around “media” really invigorating. Maybe media studies is at a point where it is necessary but no longer sufficient for us to simply perform a “content analysis” of a particular medium — and typically a mass media form — whether we are talking here about the meaning of a film sequence or the language of a television advertisement. At the same time, even though recent scholarship in the field of media studies has been oriented towards the question of infrastructures and logistics, to me this is also less of an expansion than it is a kind of returning. It is not simply a new academic trend. These coordinates of media, infrastructure, and logistics are nothing new in the field of media studies but have been made more urgent in recent years with the increased ubiquity of data centers, logistics hubs, supply chain management courses, and all of their coordinating softwares — perhaps complicated further by the dangerous assumption of digital media’s immateriality.

In Singapore, where I am from, I’ve always been sort of intrigued and troubled at the same time by the idea that the media does not exist in Singapore; there is no fourth estate here, simply because of the government’s rather heavy-handed approach to censorship. But while it is true that most if not all of media production in Singapore has been developed to serve nation-building imperatives, Singapore is also positioned as a global media hub, “a reliable port for the transfer and distribution of media and cultural goods such as books, periodicals, recordings, filmic products and other merchandise.” This is only possible because of Singapore’s history as a key node in global sea-trade routes, which stacks up all the way to the amount of major undersea internet cables routed through Singapore. And so Singapore ends up in this curious state where domestic media is heavily contained, while global media are circulated through and beyond the island-nation (which I suppose also fits in nicely with Singapore’s role elsewhere as the busiest transshipment port). As I am writing this, Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un’s meeting in Singapore has just been reconfirmed, and I am reminded again of Singapore’s function as a critical intermediary. The majority of the world’s media, goods, people and now, I suppose, also political diplomacy circulates through Singapore. This “mediating” function of Singapore, like all media and black boxes, does not invite much scrutiny of itself; so I am proposing in my research to think of Singapore broadly as media, and to see what we might get out of pushing such a proposition.

But I want to ask you also about your own work on global supply chains, particularly in the context of manufacturing media forms such as the mobile phone. Perhaps we could use this example of the telephone as a way to talk more in detail about the global assembling of factory assembly lines, sites of extraction, and coordinated supply chains. How do we think about this system of assembling, and what are some of the efforts from both the manufacturers and scholars to audit and trace it?

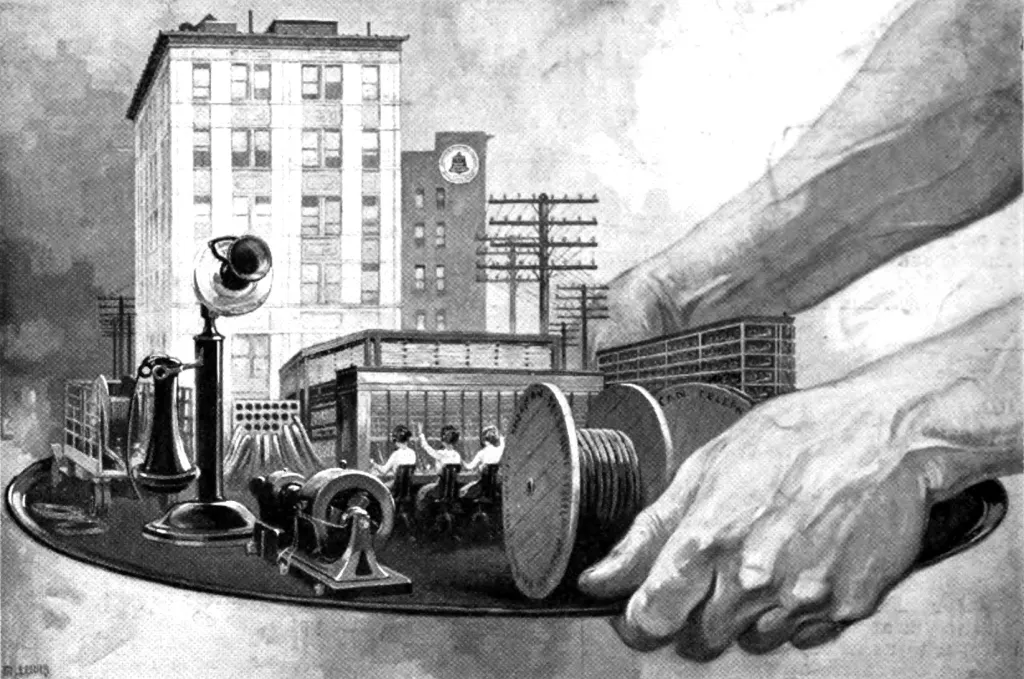

MH: The first thing we need to acknowledge is that modern objects are unbelievably complex. In many respects they are the material instantiation of forms of knowledge and patterns of development that stretch back centuries. As a consequence, they can seem frustratingly opaque, with a hostility to interrogation that frequently serves to obscure their origins and operation. The result is that the complexities of our material infrastructures and circulatory systems have become almost entirely removed from human sensibilities. These are, one might say, networked objects. Not only within digital networks, but as entities inescapably enmeshed in the material network of their own assembly. And perhaps none more so than our mobile phones. They are housed in plastics molded in Ecuador, Saudi Arabia, and Russia, littered throughout with metals — gold, copper, tantalum, tin — drawn from South America (in places like Chile or Brazil) and Africa (from South Africa and the Congo). These myriad and precious ingredients move through countless ports, refineries, and warehouses as they are identified, gathered, processed, and assembled. The tiers of the supply chain might reasonably involve hundreds of companies and thousands of workers, even to produce a single part. It should be little surprise that any inventory of such a globally dispersed (and administratively disjoint) object would struggle for understanding and accountability.

When I started looking at global production in 2006, the smartphone was just one of a new class of embedded computing devices. These consumer electronics were not only more complex than what had come before, they required more complex constituents for their construction. Being at a place like MIT where we were prototyping all sorts of these kinds of devices, understanding this was less of an investigative process than it was a simple fact of design. How do you know, as a designer, where the pieces were coming from before you put them together? And, of course, what the impact of that assembly actually was. This led to the development of Sourcemap as a way to trace supply chains, to figure out how we might evaluate them along social and environmental dimensions. At the same time, there were accounts coming out that seemed to reveal a lot more about what was going on in global production. We started to see mobile phones capturing video and images from production sites like the factory floors in Shenzhen or the artisanal mines of Bangka Island. And new designers, who hadn’t been a part of large-scale global production, were producing accounts of their experience actually getting a product made. There were blogs about visiting factories and seeing the impact of design decisions directly on the line, reading new environmental and geographic concerns into the productive network. For a lot of people, this was a discourse on assembly that hadn’t ever really been seen before.

The turn to logistics began with questions about the impact of globalization, as investigations into the networks underpinning these processes. This includes work by artists like Allan Sekula, but also journalists and activists looking at companies like Foxconn, or the lives of the logistical laborers working in ports and warehouses. You can see this in popular books like Marc Levinson’s The Box (2006), and Rose George’s Ninety Percent of Everything (2013), but also in the work of sociologists Edna Bonacich and Jake Alimahomed-Wilson, who carved out a picture of the lifeworld of logistical workers, and, years later, their means and methods for resistance (Alimahomed-Wilson and Immanuel Ness’s recent Choke Points, 2018). In anthropology, decades of work on trade networks have found new articulations in the language of the supply chain, perhaps most notably in Anna Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015). Architects and urban planners, long interested in the material infrastructures of distribution and assembly, have begun to directly confront the organizational logics of logistics in project’s like Jesse LeCavalier’s The Rule of Logistics and Clare Lyster’s Learning from Logistics. Similar work has followed within geography and design, with Deb Cowen following the landscape of contemporary distribution back to its origins in the legacy of the Napoleonic campaigns in her The Deadly Life of Logistics (2016), or with Craig Martin’s Shipping Container (2016), which presents logistics not just as an organizational method, but as the overriding theory of global civilization. Even media and communications studies has turned towards infrastructure, distribution, and production to grapple with the material conditions of media. In academia we are seeing conferences, syllabi, and working groups increasingly organized around this critique. Outside of it, we have seen journalism move from the sweatshop labor pieces of the nineties to comprehensive investigations on outsourcing, worker rights, and corporate responsibility. Activists have drawn targets on companies like Apple, Samsung, and Nokia. Legislation related to supply chain transparency has passed in Europe and the U.S. Corporations have incorporated the critique into their practices and their reports.

One of the reasons for organizing Supply & Command was seeing just how ubiquitous media objects are in these accounts — from legal contracts and shipping manifests to satellite phones and radios. Media is not just a logistical production in the form of something like the mobile phone; it is a critical component of the logistical operation itself. I would suggest that we need to follow work on the media of logistics, like Alexander Klose’s Container Principle (2009) and Ned Rossiter’s examination of logistical software systems (Software, Infrastructure, Labor: A Media Theory of Logistical Nightmares, 2016), to understand the ways in which logistics is, itself, a practice of mediation. One way to think about this is to say that there is no such thing as a supply chain. If you were to go out and actually look at the network of production, the system of assembly as you say, you find this spectacular spider web of people, places, and pathways. What we call the supply chain is a kind of approximation of a single moment in that network. It’s when the nodes of global assembly crystalize into configuration, just long enough for a productive pulse to reverberate throughout the network.

The supply chain is a way to conceptualize this process. It’s a way of thinking, in other words, an epistemology for modern production. What we call supply chains are collections of geographies, metals, minerals, parts, and productions. They are ordered and organized in particular ways. Corporations know their suppliers. Those companies know their suppliers. That knowledge is constituted by a socio-technical apparatus made up of specifications, inspections, contracts, and personal relationships. The supply chain is just the social network for stuff. In any given act of assembly, a company has arranged to buy some parts from one company, some from another, and so on. Each supplier supplies up toward final assembly. And you aren’t meant to follow them down. It is as much a way of unknowing as it is a way of knowing. If you look at one of these “suppliers” you might find that they are only really a wholesaler. The companies that supply them, in turn, are getting parts from any number of others. With increased specialization and the flexibility of modern distribution, even the most basic of investigations can open up a Pandora’s box of actors and assemblies, parts and places. By the time you get to something as complex as a mobile phone or a computer, the number of steps and sources can be staggering. What we call the supply chain is really just a mediative operation for the whole of the world, from Singapore to Cincinnati.

Kenneth Tay is a M.A. candidate in Media Studies at The New School. He writes and researches on media infrastructures and logistics in the context of Singapore.

Matthew Hockenberry is a media historian and technologist who writes regularly on the state of global supply through the lens of its most emblematic objects. This has taken the form of research and work published on the global infrastructures of food processing and food production, the assembly and distribution of tin solder for the global electronics business, and the global manufacturing of telephones and telephone parts. His PhD dissertation at NYU’s Department of Media, Culture, and Communication developed a history of logistics, tracing the impact of media forms and material practices on decentralized production and the mediation of manufacture throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century. He recently co-organized the conference Supply and Command: Encoding Logistics, Labor and the Mediation of Making at NYU.